Middle East

I come from a family of first responders, police chiefs and firefighters, and am lucky to have grown up in a culture of selflessness, volunteerism, compassion—and also privilege.

We are no stranger to tragedy. For example, when my mom was a volunteer paramedic, she suffered permanent lung and nerve damage after inhaling the same chemical that killed 16,000 sleeping civilians in Bhopal, India in the world’s worst industrial disaster. The doctors told her that because she’s never smoked, her lungs were more susceptible to the toxic gas and even though she is left with a whole host of medical problems, needless to say, she is lucky to be alive. (I’ve written more about that incident here)

But, if we weren’t well off per se, we got by. And, by virtue of our birth, we live in a land of liberty, wealth, and unparalleled promise, so it is our duty to be active allies: first, by listening and bearing witness and then by tending the seeds of justice and resilience.

Heeding the call, I traveled to the Middle East in the summer of 2018, where I followed in the footsteps of countless conquerors and multiple messiahs. Being neither of these, I hoped my moral compass would help me navigate Mediterranean headwinds, if not to the promised land, then at least to a place where I could help heal and empower.

I came to the Levant to learn peacebuilding strategies, listen to the ignored stories of long-suffering people, and, ultimately, help support refugee children who have only known a world of fear and bloodshed. To break the spiral of silence, my work, which was organized by the Center for World Religions, Diplomacy, and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University, would take me to Jordan for one week. But before touching down in Amman, I decided to first visit Turkey and Cypress—neither country a stranger to strife—on my own to learn more about the millennia of conflict and the enduring human spirit.

ISTANBUL

Lygos, Byzantium, Nova Roma, Antoniniana, Constantinople, Istanbul. Like the rings of a redwood, the Queen of Cities is a living symbol of the evolutionary power of hope. The many names that have adorned it over the years have come and go, but the solid shores of the Bosporus—the narrow strait that connects the Black and Marmara Seas and separates the mythos of East and West—have been coveted for millennia.

Since Greek settlers laid roots in the area some 2,700 years ago, the cool blue currents of the water have been both a blessing and a curse for the Turks. On one hand, they have enabled Istanbul to take full advantage of its strategic position where East meets West. Venetian and Genoan traders have made fortunes swapping wares, stories, and sometimes intimacy with their Eastern counterparts. The labyrinthine halls of Istanbul’s most fabled markets, the Grand Bazaar and the Spice Bazaar, have attracted scores of merchants dreaming of striking it rich.

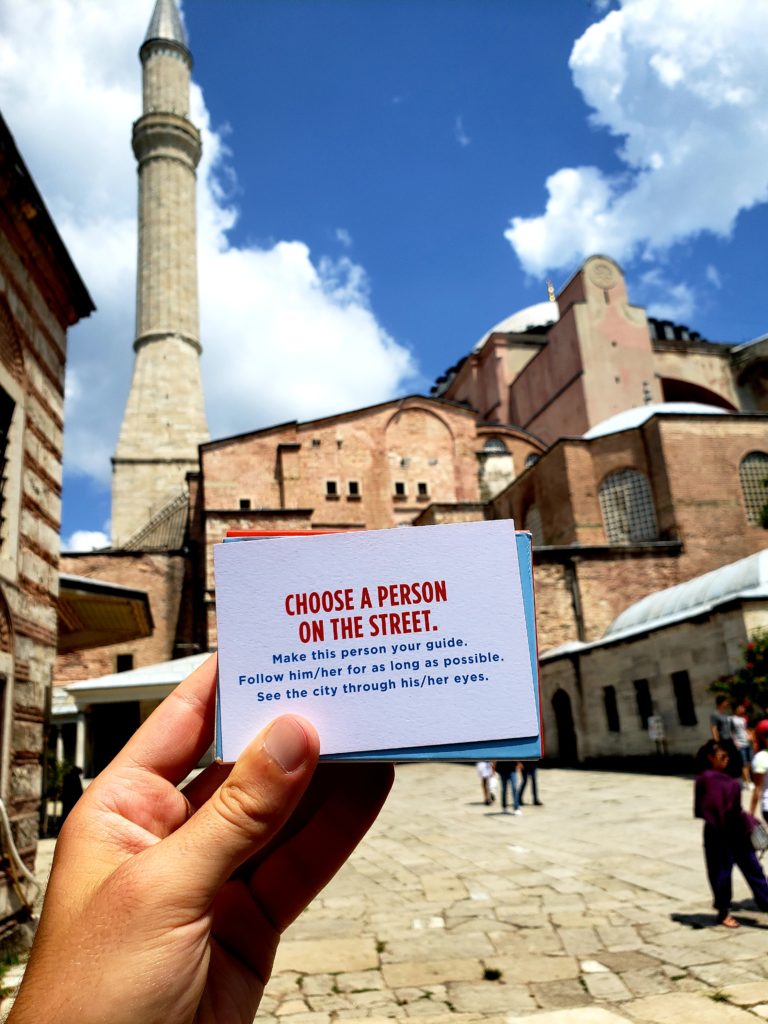

But since it’s humble beginnings, the seas that surround the city have also encouraged invaders to test the city’s defenses on countless occasions. Goths, Macedonians, Russians, and European crusaders—to name but a few–have all tried to sack its harbors and relinquish its riches. Many times, they have been rebuffed by the impenetrable cliffs and formidable forts, but timid men rarely make history. One of the bravest, Mehmed the Conqueror, commanded the once-unthinkable conquest of the city in 1453, which resulted in Constantinople becoming stronghold for Islam. With the success of the siege, the golden icons of the Hagia Sophia were papered over and replaced with dramatic black hadiths. Despite numerous fires, earthquakes, and conquests, the famed dome of the Hagia Sophia has withstood the test of time, crowning the city’s skyline for almost 1,500 years. Now under renovation, the cathedral-cum-mosque-cum-museum displays both, underscoring the complex, cosmopolitan culture of Turkey.

By its sheer attraction, it has always been a city in transition. Like the lost cisterns under the city, there is a reservoir of tenacity buried beneath the Turkish psyche along with the remnants of empires past. For centuries, the city has stood and withstood. And it will doubtless continue onward.

Today, the certainty of the current brings comfort to the 15 million İstanbullu who seek reprieve from the heat. Whether on holiday in the Princes’ Islands or enjoying a sunset cruise from Eminönü, the Golden Horn remains one the most enduring monument that defines life in the city—and it will continue on long after our generation is gone.After getting lost on the steep climb up to the Yoros Castle, a strategic marker at the mouth of the Bosporus and Black Seas, I stumbled upon a lovely little graveyard halfway up the bluffs. Not a bad place to spend eternity…or to rest from the midday sun.

CAPPADOCIA

Ten hours inland from Istanbul, the landscape varies drastically. After nearly losing my overnight bus at a bustling mountain rest stop, I awoke to the warm glow of sunrise igniting the rusty red mountains, which were reminiscent of the American west—or a Martian moonscape.

From the craggy canyons and whimsical karsts to the ancient cave churches and towering minarets, everything about Cappadocia is straight out of a fairy tale. No photo can truly capture the stunning beauty of this region, but I gave it my best shot from the basket of the many hot air balloons that grace the sky. With views like these, it is little wonder that Cappadocia is one of the top places in the world to take to the sky.

The terrestrial view is equally amazing and all the more memorable after you race through narrow mountain passes to catch the fast-fading sunset. After his ATV broke down, my guide was forced to radio in a replacement quad and we weren’t sure if we would be able to make it in time to see the breathtaking view. Fortunately, another guide rushed in a replacement and we set off for Sunset Point with mere minutes before nightfall. Fueled by adrenaline and kicking up dust, we blew through secret shortcuts and windy trails to beat out the surging throng of tourists just in time to run up the final hill and claim the best seat in the house.Gallery of Landscape

Between its enchanting fairy chimneys, copper-colored canyons, and free-floating balloons, it’s no wonder why Cappadocia is such a popular backdrop for Turkish newlyweds. I must have seen at least 10 brides in my day of wandering around the UNESCO World Heritage. From saying “I do” to yelling “Lights, camel, action,” the beauty of the brides led me to learn the true meaning of çok güzel! Dressed all in white, it was surreal seeing the juxtaposition of the lovely ladies with the lunar landscape all around.

ANTALYA

Many Turkish honeymoons take place in Antalya, a resort city on the Mediterranean coast and home to many ancient relics including Hadrian’s Wall, which is still standing since being built in the year 130. Also known as the Turkish Riveria, the city attracts visitors from all around the world and boasts crystal clear waters to cool off in on 100-degree days. Cappadocia and Antalya both prove that the allure of Turkey lives on, not just in the cultural capital of Istanbul, but throughout the country. The enduring geographic, economic, and spiritual significance of these tourist hotspots suggest that the flame of intrigue in the country cannot be extinguished and can be used as a lifeline to stay afloat during the turbulent financial times Turkey is once again facing.

CYPRUS

On my last day of vacation before heading to Jordan, I decided to make a quick day trip to the capital of Cyprus, the last divided city left in the world now that the Berlin Wall is history. Facing long-simmering hostility between Turkish- and Greek-Cypriots, the 1.1 million residents of the island agree on little, save that an ongoing conflict exists. Every facet of life is contested and, depending on which side of the divide you stand, the city is either called Nicosia or Lefkosia.

My plane landed in Lefkosia on the Turkish-Cypriot side of the border, which considers itself independent, but is not formally recognized by any country except Turkey. Decades of sanctions and economic stagnation have stretched the average household. Infrastructure is lacking, but the breakaway region is surprisingly orderly and welcoming to tourists.

Ledra Street, the main thoroughfare that connects the renegade region to the Republic of Cyprus, which is a proud member of the European Union, exposes the stark divide. As I walked closer to the UN-imposed de-escalation zone, a DMZ-like barrier in the heart of the city, the tension was unmistakable. Between 1974 and 2008, there was no legal way for civilians to visit the other side along the street, so even the creation of a border crossing at all is major progress. But as I edged closer, border guards and bystanders began shouting wildly at one another and I worried the situation would get out of hand. In no man’s land, circled with concertina wire, makeshift barriers, and armed soldiers in all directions, I spied defiant graffiti that cried out for peace: “Your wall cannot divide us.”

On the other side, luxury shops and breezy restaurants dot the avenue, which could have been plucked from Paris or Pittsburgh. I exchanged my lira for euros, recharged my phone at Starbucks, and enjoyed a cold pint with my falafel pita before exploring again. In many ways, the swankiness is a façade: a short jaunt away from Ledra Street and the “continental chic” gives way to corrugated steel shutters, radical wall scribbles, fifty-gallon drums, threatening guard shacks, and razor wire that literally cleaves whole houses in two.P

When one’s identity is wrapped in a flag, it’s far too easy to forget the shared humanity that bleeds from the wounds we inflict. And, in a trip-wire town, this realization thunders like a gunshot.

I was reminded of this fact when I made friends with the docent at a small museum. After meeting him on the street, he kindly opened the exhibits up to me early and gave me a personal tour of the rich, centuries-old tapestries that endured on the wall. We chatted about Islamic symbolism and the healing properties of aromatherapy for a long time. Before I left, he insisted that I take a collection of scented oils and herbs that he prepared himself and wished me good luck in the rest of my journey.

Instead of concertina wire and anarchist graffiti, it is this stranger’s generosity and hospitality that I will most remember about Cyprus.

JORDAN

After 40 hours of sleepless adventure and getting detained briefly by Turkish border guards, I finally stood at the at gate of my pre-dawn flight as excited as I was exhausted. Yet, before my next chapter began in earnest, fate decided to take the opportunity to teach me yet another lesson about war and privilege.

Struggling to keep my eyes open, I noticed a long line of covered women and bearded men undergoing yet another security check before they were allowed to board the plane. Annoyed, I asked a light-skinned airline employee why we all had to get patted down and searched again after we already went through X-rays and body scanners to make it this far. After briefly looking me up and down, he waved me around the growing queue, telling me that I am “not the type of person we are looking for” and that he “could tell by looking that [I am] trustworthy” so I can avoid the extra scrutiny. I was shocked: to him, my white skin and Western clothes make great proxies for good intentions because I was allowed to pass Go, while the Arab Muslims corralled into the makeshift checkpoint at the gate had no such Get Out of Jail Free Card.

I’d like to say that I protested, that I lectured him on the poisons of profiling, that I waited in the security queue out of solidarity. But I didn’t; I simply breezed past the onlookers and watched the mothers and fathers get patted down in front of their nervous children, haunted by a nagging question: How could I let myself abuse my privilege so casually when I’ve strived my whole life to leverage it in service to others?

My peacebuilding course in Jordan gave me answers–and hope. Led by a world-renown professor of conflict resolution and Syrian activists who are daring to fight for peace from behind enemy islands, the workshop explored how practicing self-awareness is the first step to feeling more empowered to change my thought patterns, attitude, and behavior—therefore, with conscious practice, I can reshape my neural pathways to feel more confident in standing up to injustice, which in turn, can help others around me realize that they too “have the capacity and power to evolve to turn what used to be normal into something unacceptable.” I’ve taken this lesson with me every time I set foot in a refugee camp or classroom—and I’ve cradled it every day since.

Working with children who have experienced enough trauma to fill a lifetime was incredibly emotional, yet unbelievably fun. We met the children of Project Amal ou Salam (Hope and Peace) for the first time and led art, music, and sports workshops. After 7 years of war, it was amazing to see the kids just be kids again. Immediately, they were so warm and openhearted, chasing us all around, giving us hugs, laughing, sharing crafts they made, and wanting to play. They have the biggest hearts I’ve ever seen. Case in point: we held a big birthday party and, despite some children never having the chance to eat cake before, they refused to eat it because they wanted to bring their slice home to share with their mothers. (Sadly, many are without fathers due to immigration, conscription, or casualty).

Children are the most innocent victims of war, lacking the capacity to broker peace in battles they didn’t start. Witnessing atrocities on a regular basis, they often carry significant psychological trauma, PTSD, and severe depression and anxiety. Fortunately, programs like Happiness Again provide a safe space for kids to develop healthy coping skills and recover. The organization provides groundbreaking therapy programs using art, music, exercise, and one-on-one counseling. It broke my heart to hear the children talk about the tragedies they’ve witnessed. For instance, one child told the group he is no longer afraid of seeing people get shot anymore; another child would pretend to bury their parents in the sandbox as a way to cope with his unspeakable grief. The amazing teachers and psychologists teach children nonviolent techniques to welcome fear instead of fighting it and I cherished the chance to do yoga with the kids and watch as they told the teacher pretending to be a monster that they accept and welcome it. It is truly inspiring to see organizations like Happiness Again, which is led by volunteers from Syria, provide psychosocial support to more than 1,000 kids who will one day grow up to be leaders and build peace for the next generation in their own communities.

For the most vulnerable and powerless, even the smallest act of agency can have a huge impact. Inspired by a friend who moved to a remote region of Peru and formed a nonprofit designed to give children with no formal education access to cameras to make their own documentaries to feel empowered and express themselves, I felt compelled to let the children use my cellphone camera to take pictures of anything wanted. It is critical to allow children to express themselves because sharing one’s point of view—even if it is a simple selfie among friends—is a fundamental human freedom. I will forever cherish the photos and videos the children took with their smiling faces beaming bright and am glad that I was able to provide them with a means for entertainment and a sense of control in an otherwise precarious predicament. Like the child-friendly conflict resolution techniques taught through arts, sports, and music at Amal ou Salam and Happiness Again, I developed a greater appreciation for using photography—one of my core passions—to help heal trauma. Moreover, by sharing the happy photos with social media networks, I helped dispel the myth that refugees are terrorists and criminals, while helping to humanize the victims of war and developing more empathy and compassion amongst my American friends and family. Over time, small acts of compassion and agency build up to create enormous impacts and power.

Helping empower others has also helped me realize my own power––something that I far too often forget. As an introvert, I prefer working quietly behind the scenes instead of being the center of attention. But standing alone in a room full of 60 screaming children whose mothers were discussing what rights should be included in a new constitution, I felt completely confident and in control. Because there were no toys in the overcrowded room, I used my instinctive creativity to turn a laundry basket into a basketball hoop and old pieces of paper into projectiles. The kids were thrilled and we eventually had a raucous “snowball” fight. Looking back on this activity, I feel more confident in my ability to exhibit high energy and work without any clear guidance when I need to.

Furthermore, by speaking about my experiences to the group, I realized that I actually gained one of my most special memories in that room. After the chaos died down and we swept up the paper balls that littered the floor, I noticed a small girl—who had been so sweet to me earlier—crying by herself in the corner. Having felt isolated and excluded in the past, I made it my mission to make her smile. Though language barriers prevented us from understanding each other, I knelt to her level and started to act silly when it was clear she wouldn’t or couldn’t tell me her problems. When she started laughing (undoubtedly at my terrible Arabic accent), I asked her and the growing group around her to teach me the names of the colors in Arabic. Soon she was delighted and included in the group, and I realized that my passion for helping others cultivate their own agency needs to be directed inwardly if I want to grow. After we left the women’s center, it made me feel really good some of my other classmates told me how wonderful I am with kids. I realized that not only did I inspire the children, but I also inspired the changemakers around me. In turn, they inspired me, jumpstarting a virtuous circle that can push us towards meaningful and lasting impact. H

Beyond providing refuge to over nearly 800,000 civilians who fled chemical attacks and carpet bombing, Jordan is home to a very rich history that provides the backdrop to life’s special moments, both big and small. Built atop the remnants of Roman ruins in the 8th century, the Umayyad Palace overlooks all of Amman and is a prime spot for graduation photos. I had the pleasure of chatting with these proud young women as the sun set behind the hillside houses and the call to prayer echoed all around. Lifelong friends, their degrees are in education, engineering, and German language—and, amazingly, they navigated the jagged steps in heels with incredible grace! As nightfall descended in the desert, I spied several emerging superstars playing soccer amongst the ruins. Giddy with glee, the children made a makeshift “net” out of the Temple of Hercules, one of the oldest and perhaps most important of the Roman ruins that overlook Amman. Despite the shadow of war all around, many youth like these two groups have a bright future ahead of them.

PETRA

No trip to Jordan would be complete without trekking to Petra, one of the new seven wonders of the world. Long the capital of the Nabataean’s rich trading empire, the city fell to the Romans before falling into disrepair and eventually obscurity for hundreds of years. Against all odds, the ancient city stands as an oasis in the rusty-red Arabian desert. Entering through al-Siq, a narrow sandstone slot canyon, the splendor the city’s churches and tombs slowly reveal themselves, eventually reaching a crescendo with the dramatic emergence of al-Khazneh (the Treasury). As regional trading patterns shifted away from this hidden heartland, Petra was all but forgotten by the world, save for the Bedouin tribes whose nomadic lifestyle occasionally brought them through the area. Today, many have settled in the area and are generously supported by the government and the substantial flow of tourist dollars. Like the chiseled mausoleums carved into the cliffs—indeed, like all of the people I met on this adventure––the Bedouin represent a tough, timeless spirit that has endured—and will continue to endure hamdullah.

CONCLUSION

Traveling teaches you no person, no place has a monopoly on tragedy and triumph. After connecting to my return flight in Frankfurt, a city that saw its medieval city center blasted to bits by the Allies in WWII, I had a chance to put my peacebuilding skills to the test again.

I sat next to a tobacco-chewing, obscenity-dropping, Trump-supporting, Blue-Lives-Matter-hat-wearing, former soldier with PTSD who told me in sad detail how he had to be Medevacked out of Afghanistan and institutionalized for 3 months because of a breakdown that stemmed from grisly acts of violence perpetrated by his fellow soldiers against children. He told me how he often wakes up in a panic, how he pops Percocets to numb the pain of a burdened back and troubled mind, how he lives in the mountains with only his arsenal of guns to keep him company. And, in a frightengly matter-of-fact tone, he told me how he knows that he will one day commit suicide because he has so little hope for the future.

By talking to this former soldier, I realized that “resilience suggests that the state of mind matters more than anything” and that cultivating healthy coping mechanisms is fundamental to working through conflicts, both internal and external. Even though, on the surface, this man stood for almost everything I’m against, I hoped that listening to him with empathy and firm compassion would inspire him to seek therapy or at least take small steps to change his mindset.

And so, instead of napping or watching movies, I sat patiently and asked poignant—yet nonjudgmental—questions to help him manage his emotions and see his situation in a different light. I told him about a former Marine I knew who got married and had a baby at the age of 50, showing that there is hope for lifelong bachelors to settle down. I told him about our work with the children in Jordan and how the trauma-informed care at Happiness Again helped the children develop healthy coping skills. I recommended Dr. Marc Gopin’s book, Healing the Heart of Conflict, as a good starting point for self-reflection. And I listened happily as he confided that he is not completely alone in the world: he has one best friend who he trusts with all his heart and, what’s more, he spent over 100 euros buying German chocolate to spoil his “niece and nephew.”

By the time we landed at Dulles, he was incredibly happy to be back in the United States and rushed off to his connecting flight, leaving neither his name nor number. I’ve thought about him every day since.

Even though listening to someone is such a small action, I knew I did the best I could with the resources I had, and it is a series of small actions that form the foundation of positive change. And so, even though I don’t have all the answers nor all the confidence in the world, I feel slightly more optimistic and empowered to develop myself, to improve my mindset, to open my heart, and to feel more prepared to address the conflicts I face every single day.

The lessons I learned in the Levant motivated me to keep making the positive changes in my life that help me feel more fulfilled; cultivate habits that improve my own ability to be resilient; create lasting positive change through steady, small increments; and, finally, inspire those around me to do the same—thus fueling a virtuous circle that will continue to spur peace, prosperity, and progress long after I’m gone.